- Introduction

- Image Gallery

- Historical articles1.

- Newspaper stories

- Selected oral history interviews

- Henry Curtis Letter about growing hops

- Complete list of other interviewees who talk about growing hops in Franklin County

- Other other documents

2. Image Gallery

[flagallery gid=22 name=Gallery]

3. Historical Articles

Article on Hops

by Frederick Seaver*

In 1887 the county produced its record crop — estimated, with probable accuracy, at over 17,000 bales. Since that year there has been an almost continuous decrease both in the number and extent of the yards, and of course in the quantity of hops harvested. Formerly yards of twenty to thirty acres each were common in Bangor, Constable and Malone, and many were a good deal larger. Robert Schroeder, a New York city hop merchant, set out yards in Duane of two or three hundred acres.

*Page 45

“Historical Sketches of Franklin County And Its Several Towns |Seaver,Frederick J | |1918 |J.B Lyons

Company |Albany, NY

4. Newspaper Articles

Malone Palladium Jan 7, 1892

New Hop Statistics

From the recent census bulletin on Hops some figures of interest may be drawn, The regular census year was 1889, but the figures for 1890 have been obtained, and for comparison some data for previous years are added. A few of the figures are given here. The acreage was as follows:–

1879 1889 1890

- Total United States 46,800 50,212 48,962

- New York 39,072 36,670 35,552

- Oneida Co. 5,937 6,002 6,180

- Otsego Co. 9,118 7,749 7,679

- Madison Co. 6,076 6,956 7,040

- Schoharie Co. 5,871 5,563 5,689

- Franklin Co. 2,075 2,330 2,796

- Clinton Co. 64 119 94

- Jefferson Co. 269 115 112

- St. Lawrence Co. 331 185 140

The crop in pounds was as follows –

1879 1889 1890

- Total United States 26,546,378 89,171,270 36,872,854

- New York 21,628931 20,068029 17,861,240

- Oneida Co. 4,075,651 2,708,410 8,065,000

- Otsego Co. 4,441,029 3,704,841 3,065,000

- Madison Co. 3,823,962 4,094,440 3,865,527

- Schoharie Co. 2,982,873 3,148,885 2,758,922

- Franklin Co. 1,083,350 1,106,126 1,230,070

- Clinton Co. 30,482 44,879 95,250

- Jefferson Co. 135,955 33,728 34,452

- St. Lawrence Co. 177,866 49,487 41,445

No other county of the State has reached the million pound line except Montgomery in 1879. In other States five counties have passed the, line. The above figures, it should be said, differ somewhat from those collected by Franklin county dealers. From these tables the following figures are deduced: The average product per acre in pounds and dollars was:

1879 1889 1890 1889 1890

- The United States 567 780 753 80.85 226.82

- New York State 554 547 502 60.27 170.68

- Oneida Co. 686 617 500 67.04 167.50

- Otsego Co. 487 606 510 68.29 178.51

- Madison Co. 629 589 618 64.22 207.18

- Schoharie Co. 508 586 485 64.60 186.50

- Franklin Co. 522 378 440 34.40 152.50

- Clinton Co. 475 377 1,013 54.04 309.05

- Jefferson Co. 505 337 308 30.07 83.93

- St. Lawrence Co. 537 267 296 32.31 101.91

The value of the crop is not given for 1879 and earlier years. It appears that the few Clinton county hops, of 1889 brought over 14 cents per pound, while the Franklin county crop averaged nine cents—the average for the State being 11 cents.

The number of pounds raised in 1890- for each inhabitant in the principal counties was

- Oneida Co. 24.9

- Otsego Co. 76.0

- Madison Co. 101

- Schoharie Co. 94

- Franklin Co. 32

- Pierce Co. Washington, highest outside of New York State 71.2

‘But the most striking feature of these figures is the low return per acre in Franklin County as compared with other counties. All persons who are not infatuated, with the dream of sudden wealth from hops will find food for reflection in these figures, and will wonder why this county ranks so low. They will ask whether the last few years have been especially unfavorable to this county ? Is the soil not well fitted for hops ? Are the winters too long and the summers too short? Are the varieties usually grown here more tender, more liable to injury from insects or mildew, or otherwise less productive than those of other parts of the State? Are growers, although perhaps neglecting the rest of their farms, putting too little labor and too little fertilizer on their hop yards? Are they behind the times in their methods of cultivation and picking ? When the averages are obtained from nearly 3,000 acres, it is evident that the failure is too general to be due to any few men or farms. It is so widespread as to call for a serious consideration of its causes among hop raisers, many of whom should, either improve their methods or go out of business.

From the: Malone Farmer July 8 1931

5. The Hops Industry in Franklin County

By F. L. Turner

With the single exception of the dairy industry that assumed large proportions in the last twenty years the growing of hops held first place for many years in Franklin county. Hop growing in this section reached its peak between 1880 and 1890. Some towns did not take kindly to it but in the main this acreage was distributed throughout this territory, although the towns immediately surrounding Malone held the larger acreage.

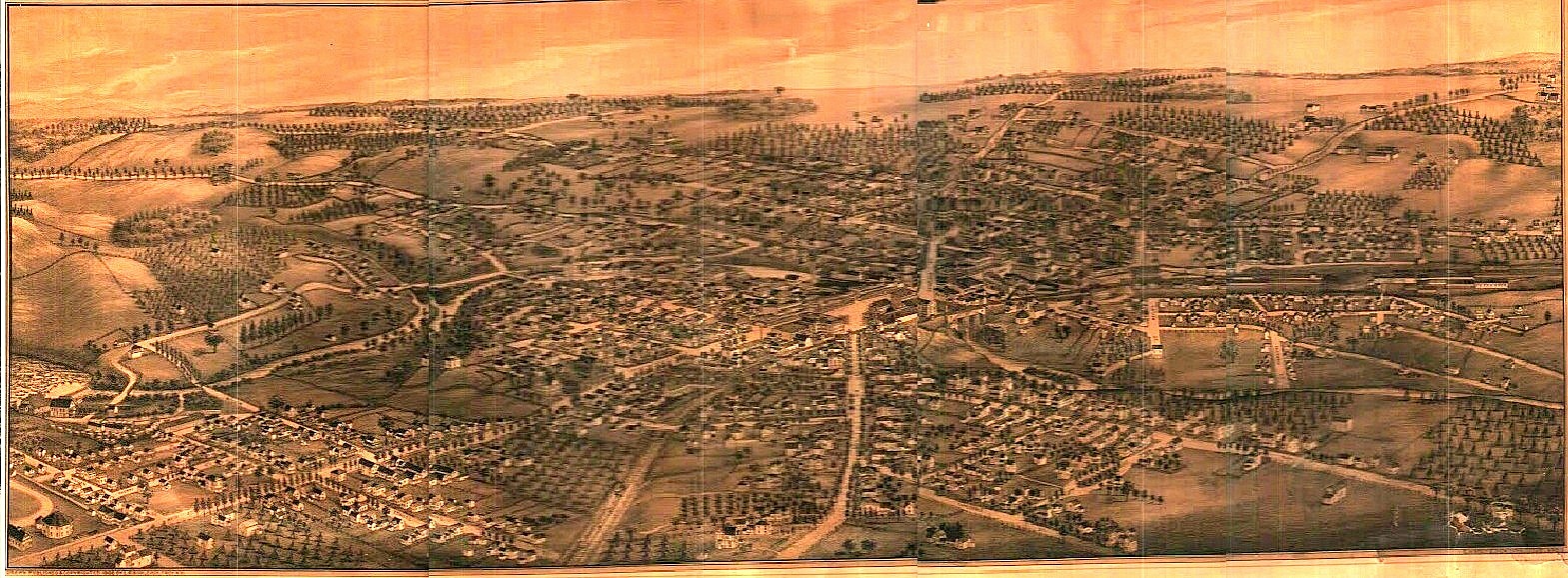

The crop required more than the average amount of fertilizer and cost much more to produce than the ordinary farm crop. The hills were set about six feet apart, making about 800 hills to the acre. After setting out the roots it took two years to produce a crop. Cedar poles were largely used although in some cases spruce was employed. The cedar swamps in the county, notably Bombay, furnished a good many. Some were shipped in from Clinton county. The price, laid down in Malone, was from $70.00 to $90.00 per thousand. These poles were about three inches in diameter at the butt and from eighteen to twenty-five feet long. Following hop picking they were stacked up in the fall, as seen in the picture.

A pointed cone-shaped iron bar with a long slim handle was used to make holes for the ‘poles that were set two to each hill, the holes being slanted a little to spread the tops of the poles slightly. The poles were set early while the ground was wet.

My father had a yard on the farm and also on the five acre plot of ground where we lived on West Main Street. He bought a good many spruce poles in Duane from William H. Sprague who furnished them all cut and trimmed in piles convenient to woods roads at $1.00 per hundred. I drove team and hauled a good many of them a distance of 18 miles when 12 years old.

After a yard was well established all the small roots that spread out in all directions had to be cut off close to the main body of large roots every year. These in turn were sold to prospective hop growers or where new yards were to be set out by those still in the business. They brought about 50c a bushel. They were cut up into -six –inch lengths and planted two pieces to a hill.

As the vines got long enough they were tied to the poles. Two of the strongest vines were used and women and girls mostly from the farms or surrounding neighbourhood were thus employed. Care had to be taken to start them the right way as hop vines grow around with the sun and cannot be made to grow against the sun like pole beans. These women had to go over the yards three or four times as vines would get off, some would not be long enough to start the first time and occasionally the head on a vine would be found broken off and another vine had to be substituted.

After two vines to each pole were growing vigorously the dozen other vines spreading around on the ground were pulled out to let all the strength go into the four vines. After these had reached the top of the poles, or nearly so, the leaves and small shoots were all cut off up about four feet from the ground.

Frequent cultivating and hoeing were necessary to keep the yard clear of weeds. Fertilizer was put on late in the fall in the shape of manure. I t was placed on the hills and was also helpful to keep the hops from winter-killing by the ground freezing and thawing.

Picking usually started about the 10th of September and it would be a month before the entire crop would be gathered. Boxes holding 20 bushels were standard and theusual price 50 to 75c a box.

Crotches were set at each end. The boxes and poles loaded with hops, were laid about three feet above the boxes. “No large leaves or stems were allowed, but it was no easy job to make workers pick as clean as they””should. When a box was full and had been accepted two or three girls would get thrown into a box and there was lots of fun in the yards. Occasionally some large matronly women would get tipped into a box unawares who did not relish the predicament.

If the dry kiln was near, the boxes would be carried or hauled to the platform. Otherwise large sacks were used. The kilns would be fitted with two big wood stoves on the ground with no floor. The second floor would be made of slats set edgewise with about 2 1-2 inches in between. These slats were covered with a coarse woven cloth stretched tightly. The hops would Be spread from a foot to fifteen inches thick and with all doors shut tight big hot fires would be started and kept up until the hops were sufficiently dried. After the hops began to steam well, about one pound of sulphur WJW burned on the stoves to each twenty bushels of hops. I t was put into kettles and enough added to keep burning about an hour. When the hops were sufficiently dried they would be pushed into an adjoining storeroom where the floor was on the same level as the kiln.

About a month later hop pressing was started, four or five men with a press moving from place to, place, or if the yards were large the owner would have his own press.

Boxes would be placed in line at one end of the yard occupying every other row, the pickers at one box being required to pick all the hops on those two rows. This hadto be adhered to strictly for hops varied greatly in size. Then on some poles the hops would be spread along for several feet making them easy to pick. Others would be all bunched together in a big tangle and the hops would be small and slow to pick. When picking had commenced generally there was work for every person in the community. It took a good many men to pull poles, strip the vines and wait on the pickers by putting the poles over the boxes and removing them. One man would care for a half dozen boxes unless the pickers at each box were numerous. Tickets were given when a box was full and at the end there would be 1-2 and 1-4 box tickets.

The growers had to provide plenty of ready cash to pay off as soon as picking was finished. The larger growers would borrow at the bank, others perhaps at the store where they had an account, and occasionally some would be forehanded enough to have the cash in their pocket. Long credit at the larger stores was the bane of the farmer and hundreds of farms in Northern New York in early days were taken over by merchants on foreclosure proceedings. The acquaintance of every member of a family would be cultivated by the storekeeper or his clerks and all urged to buy liberally, the merchant adding, “as your father’s credit is always good.” Hundreds of dollars worth of goods were thus sold to unsuspecting young people and women that would never have been purchased if cash had been demanded. No doubt the farmer himself in some cases felt puffed up when told his credit was always good.

At the end of the first or second year the merchant would casually request that a note be given, simply as a formality, as the cash was riot needed. Later an endorser was required which later led to a mortgage. By that time two-thirds of the farm’s value was represented in the store debt.

In the end few merchants were benefitted by this sharp practice. They knew nothing about farming. If a farm was sold it meant another mortgage, it was a problem to keep them rented or leased on shares and as a rule this class of farmers were non-progressive and inefficient. As one drove about the country the farms owned by merchants could be usually spotted. Many of them in later years were vacant and growing up to brush.

I recall one farm that was taken over by a banker who had so much cash invested that he had to take the farm to save his investment. He succeeded in “saving the farm” for he has it yet for ten years it has been abandoned. I suspect he felt somewhat elated as this was the first piece of real estate of any size he had ever owned. He started la with high hopes, fixed up the house and bants, spent three or four hundred dollars in sinking a deep well, and after some persuasion put a man on the place, helped him to stock it and shared in the expense of seed grain and potatoes. For a time the tenant called and reported progress when he came to town. Finally his visits ceased, and, wondering if the tenant was indisposed, the banker hired a car and drove 15 miles to investigate.

He found his tenant not only indisposed but sick—sick of the farm, and the prospect — so serious in fact that he bad taken his family and everything movable and decamped for fields as yet unknown.

The land was not suited to grow even a fair crop, but as one drove by the sleek looking buildings and ‘Tine pump’* it caused many people to look twice at the prospect.

About two weeks before hop picking commenced the grower would start out to get the promise of neighborhood pickers. In some cases they would be five or six miles away. In that case he would send a double team on t h e hay rack for a big load and then send them home at night.

Pickers were ambitious to earn as much as they could and all the children of suitable age were pressed in. In many cases they would start in soon after daylight and men who pulled poles had to be likewise. It meant long hours and little sleep. The dry kilns had to be kept going steadily day and night. It usually took twelve hours to dry each batch sufficiently.

Pickers came from the St. Regis Indian Reservation and even as far east as Mooers and Champlain. Whole families would come with their bedding and cooking utensils. The big growers provided sheds for sleeping quarters and the smoke from numerous snacks reminded one of gypsy camps or pioneer days. Grocery and bread carts traveled early and late to all the big yards. Merchants looked forward to hop-picking time when a flood of ready money was in circulation. The pickers bought their year’s supply of flour, pork and other staples. Some families would earn as much as $150 in a month’s time.

The yield to an acre varied from 400 to 800 pounds in Franklin county. Other counties in New York state extensively engaged in hop growing were Otsego, Schoharie, Madison and Chenango. The village of Waterville was the seat of hop culture in the southern part of the state and a paper with latest quotations was issued from there for many years.

At the height of the industry in Franklin County from fifteen to eighteen thousand bales were produced yearly, the bales averaging around 180 pounds. When pressing, two men would stand in each end of the narrow press and tread persistently until the press was full and they were doubled up like jack-knives. It took five yards of hop sacking for each bale. Thus about 90,000 yards of sacking was required yearly besides the amount that was used for sacks. The latter, however, lasted many years. The quantity of brimstone required yearly was 108,000 pounds. The store conducted by W. W, & H. E. King, and later William and J. H.King, were extensive dealers in supplies, as well as JD. Dickinson & Co., Hubbard & Mallon and several others. The Kings and D. Dickinson & Co. were large buyers of hops for many years.

During the early years prices were more nearly stable, averaging from 30 to 50 cents a pound. In 1882 the price went abnormally to $1.00 to $1.10 per pound”, mostly the result of was speculation. Some farmers that sold for 60c or 75c per pound became so excited later that they bought their neighbour’s crops for 90c to $1.00 per pound, and many of these same lots were later sold for 25c a lb.

In some years growers would refuse to sell and as the price kept dropping would carry their crop over to the second year, and in some cases for three or four years. These would deteriorate in quality and were finally sold at from four to six cents a pound. In one case I knew of a lot to be sold for 3 cents and in occasional cases they were used for horse bedding. In some cases where lots were owned jointly much friction developed where one party wanted to sell and the other was determined, to hold out for a fabulous price, Henry and Deforest Hickok had this experience. The latter was determined and did sell when the price reached $1.00 but suffered the jibes of his brother for years afterwards because the price went to $1.10.

It was the general opinion that more farmers and big hop growers were ruined financially that year than at any other period of the hop industry. In the end, except for a few, the farmers made little or no money. It was an expensive crop to raise and took so much effort and money that other farm crops were neglected. More “plasters” or mortgages were put on farms during the years when the business was at its peak than at any other period of farm operations.

When the price was so high a few unscrupulous Farmers attend to “load” their bales of hops with Various things….[can’t read all of last sentence from digital copy of the newspaper]

Article was continued on July 15, 1931

From the: Malone Farmer July 15, 1931

By F. L. Turner

Later a system of stencilling initials and numbers on each bale with other devices and the buyer keeping a record of each purchase and the numbers on each bale there were ample facilities for checking each lot purchased. I only know of one case where a Malone man was prosecuted.

During the last several years when hops were grown in the county the price was uniformly low and below the cost of production. This was largely brought about by the simple process of the brewers agreeing among themselves not to stock up with any quantity of hops but to maintain the hand-to-mouth method of buying, always at a low figure on the sure supposition that a certain number of growers, pressed by financial difficulties, would be forced to sell from week to week to keep them supplied. This scheme worked and the number of growers dwindled to an insignificant number. This happened before national prohibition was adopted. Then again it was difficult to compete with Oregon, where more pounds to the acre could be produced.

Many hop growers were temperance Men personally and when it came to a local option vote in the town on license or no license they faced a ticklish situation not only from a conscientious standpoint but from the jibes of the workers for license as well. The – latter claimed it was anything but consistent to grow hops for beer and then vote to prohibit the sale of the beverage. Some farmers solved their consciences by claiming hops were used in making yeast but even this flimsy* excuse was not shouted from the housetops. It was a subject they avoided when possible. A great many church members were in the hop-growing business. New York State had to compete with hops grown on the Pacific coast. Oregon, notably, was a big annual producer and still is in some sections. The first year’s setting there will produce a crop and the average yield is nearly double that produced in eastern sections.

During a month spent in Oregon last fall the writer observed the trend of the industry as well as the method of production. No hop poles are used and the crop is grown on heavy wire strung from heavy posts nine feet high, set about seven by fifteen feet apart. The wire is fastened on heavy hooks and can easily be let down to other hooks about four feet from the ground below which boxes are set. It was a familiar sight to observe various signs of “Hop Pickers Wanted.” The depression was not so serious as to call in the army of unemployed in that state, over which so much had been said throughout the past year.

Among the large growers around Malone these names come to mind: Andrew Ferguson and his son, Frank. The former built and occupied the home now owned by Marshall E. Howard on Elm street, while his son lived on what was recently the Sawyer farm just within the corporation limits on West Main street. Frank T. Heath who built and occupied the home now owned by the Knights of Columbus on Elm street; R. S. Brown who resided in the home now owned by Dr. A. L. Rust, corner Elm and Park streets; N. W. Warner, on the South Bangor road west of Malone; Col. Charles Durkee, Robert Cantwell who resided in the brick house just west of Mrs Harriet Grant’s residence; John S. Law, Col. William A. Jones, a mile east of the fair grounds; C. W. Breed,-Charles Spauldlng, S. B. Skinner, Patrick Donihee on the Bellmont road; Deforest Hickok and R. S. Delong. Charles Martin, of Malone and Pittsburgh, had an immense yard at Cassaville, P. Q., which was managed by David Vass.

There were scores of others equally prominent, of course, including Robert Schroeder of Duane who had the largest hop yard in the world to which detailed reference was made in my last previous article. One thing that Schroeder did, like his distinguished predecessor, James Duane. They both brought money into the town and gave employment to many. In Schroeder’s case he must have spent at least $1,000,000. and during the summer months every- man, woman and child had work in the big 650 acre hop farm.

Whether the farmers as a class benefitted by the hop-raising era is open to question. No doubt a few did where they were uniformly lucky in selling at the right price.

Practically all the big growers lost money for they were usually speculating as well as growing hops and in 1882 bought largely on a falling market. It has been repeatedlystated that .more farms were mortgaged because of the hop industry than for any other one cause. On the other hand it brought millions of money into the county and it was no doubt better distributed than the same amount could have been in any other possible way.

There were several local buyers who operated on one-half cent a pound commission. D. Dickinson & Co. and later W. D. Warner, William King, John Slattery, Isaiah Gibson and others. Samples were submitted to their city headquarters and on advise as to what they would pay there was a scramble to get to the big growers first. The outside buyers who came to Malone were H. V. Loewi, New York; S. & F. Uhlmann, New York; Lilienthal Bros., New York; Chas. Ehlermann Co., St. Louis; May & Co., Albany, and Kenyon & Saxton, of Oneonta, N. Y.

There were practically no hops grown in St. Lawrence, Clinton or Essex counties. It came to be an axiom that when a farmer came to Malone with plenty of hop dust on his boots during the banner years his credit was good. When prices were low he needed to keep his boots nicely shined.

The writer is indebted to Mrs. George C. Parker for the excellent picture of a hop yard appearing in connection with this article. It was taken by Fay & Goodell, of Malone, for stereopticon use about fifty years ago when those little interesting contrivances could be found in every corner whatnot in this North Country. The home that could not boast of a stereopticon and a set of views was considered decidedly out of date.

Hundreds of similar hop yards could be seen Within a half dozen miles of Malone. The small boys’ job of sawing up eleven million, two hundred thousand- hop poles into summer fuel after all the yards were abandoned was the cause of many youngsters indulging in their first cuss words. For many of the details in this article I am indebted to W. D. Warner and John H. King and thank them sincerely.

6. Selected Oral History Interviews

Growing Hops in Westville & Constable

Mr. J. Fred Maloney

1889 – 1977 Interviewed by: William Langlois, Recorded: September 4, 1970

Mr. Maloney: I went to working by the day for the farmers at fifty cents a day for ten hours. And I was just a boy. In that time this was all hop country here and when it come to grubbing hops.

Mr. Langlois: What’s ‘grubbing hops?’

Mr. Maloney: Well, the hops come up like this, stalks and you’d grub them all out, except you leave four or so of the best stalks to go up around the pole–the rest you took out and you could use them to set up another hop yard with, you see. But as I say when it come to grubbing hops, or anything else, the men did that but I was right with them and, of course, I had to keep up with them which I tried to.

Mr. Langlois: Did you?

Mr. Maloney: Oh, yes! Because I wanted that fifty cents a day!

Mr. Langlois: What else did you do in the hop yards?

Mr. Maloney: Well, when it came time to harvest the hops, I’d pull poles.

Mr. Langlois: Meaning? What would you do when you ‘pulled all the poles’?

Mr. Maloney: Well, at that time they set two poles into each hill, and when it came time to harvest you’d cut the vines, and pull the poles out of the hill and lay them over each box; a box would hold twenty-four bushels and there’s a crotch stick like that in the end, and you’d pull the pole with all the vines and the hops on it, lay it across that thing like that, over the box, and the women and children would sit there and pick the hops. The children would pick in a bushel basket or a box or something like that, eh, and then the parents would put them into the box, but they wouldn’t let the children, because hops would settle and they wanted to pick them as fast as they could and when they put them in they was very damn careful not to sag them. Fill the box and get your money.

Mr. Langlois: Was there any care for the hops between this?

Mr. Maloney: Oh, yes.

Mr. Langlois: What would you do?

Mr. Maloney: When they started to go up the pole, I had to tie them… tie the vines to keep them going up. And that was mostly done by women again; they’d take what we have as a feedbag today and cut a square out of it about that much and hitch it around their waist so that they could pull the thread out. You understand what I mean?

Mr. Langlois: Yes.

Mr. Maloney: And tie it up and keep on going. And, the hops had to be hoed to keep all the weeds away from the hill, and so on. And when they were all picked they’d put them into a hot kiln to dry them. That was an overhead, with slats and canvas on, and this great big mammoth box stoves down below and they’d burn sulphur and brimstone–that kills any lice or whatever was in the hops. You see, hops were inclined to have a hop lice. There was nothing dangerous about them or anything; if they got on you, they’d just fall off anyways. Little green hop lice. And, after it was all dry, they’d put them into a press and press them and bale them into a canvas–ready to be sold.

Mr. Langlois: Were there many hop yards around here?

Mr. Maloney: Oh, everybody had a hop yard! Every farmer, no matter whether it was big or small, had some hops. If it was a small, little farm he might have had an acre of hops for the family to take care of. That was the only cash you could get back then, money. Of course, a lot of them, if they had a few cows, they’d make butter and pack it in a big crock and a man from the city would come along to buy the butter; they got a little money out of that, and they got a little money out of their turkeys, but that was about the only thing. Growing hops was the only real money you could get.

Mr. Langlois: How about bees?

Mr. Maloney: Some had bees, but not too many back then.

Mr. Langlois: Did some people just own hop yards and not own farms around here?

Mr. Maloney: Well, George Cleveland[1] owned this, what they used to call the ‘Cleveland Ranch.’ I guess it was about six hundred acres and there might possibly been five hundred in hops. That was the biggest one around here. Then there was another one on the way to Malone; can’t think of the fellow’s name who owned that hop yard, but that was quite a big one too.

Mr. Langlois: Did you like working with hops?

Mr. Maloney: Yes.

Mr. Langlois: Was it a hard job, do you think?

Mr. Maloney: Yes, It was hard enough, yes. When you pulled them poles the vines would be let down with the hops and the vines on. You had to be very careful and you couldn’t drop them onto the box or it would break the box. You lift that pole and it was work enough.

THE SUN: FORT COVINGTON, N. Y – THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 1890.

The hop market is beginning to look very encouraging for farmers, as prices are on the up grade. Geo. Cleveland of East Constable, sold a choice lot of early (‘90) hops at 42c to “King & Son ” ~

Orville Langlois 1877-1975 talks about Growing Hops in Westville at the end of the 19th

Century

Orville Langlois: Oats, hops, wheat anything else for that matter.

Mr. McGowan: How many hired men did it take to harvest fifteen acres of hops?

Orville Langlois: Oh, I couldn’t tell. We generally had about three men who stayed steady at the three houses until we were boys, until we grew up, and then of course we were the hired men. We always had one to a dozen women tying hops, cleaning them up, fixing them up and keeping them up on the poles.

Mr. McGowan: Did your father have his own hop kiln?

Orville Langlois: Oh, yes. He dried his own hop kiln. I liked to dry hops; the other boys wouldn’t, so I had to.

Mr. Langlois: How did you do it?

Orville Langlois: How?

Mr. Langlois: Yes.

Orville Langlois: Well, the shop was, the hop kiln, spelled K I L N E, so called KILL, but it is spelled that way. It was eighteen by thirty-six, fourteen foot up, was a pleated two inch squares, two inches apart, and that was covered with a burlap–what they called “kiln cloth.” It was burlap and you bought enough of it to carpet the floor. And you tacked it all around, with pleats all around, and you sewed it all together to make it solid, into one piece because it comes in three foot widths or I guess it was four foot widths. And, you took those green hop buds which was picked off of the vines and spread them on that cloth, twenty inches deep. You had two big furnaces down at the bottom by the doors, two eight inch pipes that run to a chimney in the back. Run to a drum that was eighteen, twenty inches, pipes running that drum and then went into the chimney. Well, you fired that with hard wood until those stoves were red. And they had a draft on the bottom, under the sill. And you drafted up the top, according to which way the wind blew–if it was blowing from the west, well, you opened the opposite draft so that you would’t get a direct draft because you wanted to raise that heat so that it would break right through—wilt those buds until you could begin to feel them rattle through, dry, in some spots and then you had to go in there with your arms and turn that over–flip the green ones down and put the dry ones up. Well, it took about twelve hours. Intense heat. You couldn’t stay in there only just about long enough to open the door and throw in a stick of wood; it’d burn the britches right off of you. After they got where they were all dry, you understand, drier than a piece of paper, you tied them up and stored them away. After you got all done you pressed them into bales and sold them .

Mr. Langlois: Who did you sell them to?

Orville Langlois: Beer men. The men that made beer. The bitter flavour in beer comes from hops, the juice of the hops. They steeped them, used so many of the according to the gallon.

Mr. Langlois: Was the hop kiln made of wood or was there some metal in it?

Orville Langlois: No, just all wood.

Mr. McGowan: The men who bought the hops, did they live in Malone?

Orville Langlois: No, well, a lot of the time an agent did, but the men all come from City, Boston, Springfield, New York City bought a lot of our northern hops. They were awful good for growing hops. They would take a prize–northern hops.

Mr. Langlois: How much per bale?

Orville Langlois: Sold per the pound. A bale could weigh from 80 to 90 pounds. You’d average about a tonne, a tonne and a half to the acre. So, anywhere from two cents and a half to a dollar a pound. Average was about forty or fifty cents.

Mr. McGowan: How much did you pay a girl who came to help pick hops a day?

Orville Langlois: Picked by the box. A box would hold two twenty-two bushes so they got a dollar a box.

Mr. McGowan: How long would it take one person to pick a box?

Orville Langlois: Oh, If they picked a box a day, they did awfully well.

Interviewed by W. langlois & Robert H. McGowan 1970 pps. 40-43

Tapes 1-15 (no #13) and 1B-4B

7. Henry Curtis Letter about growing hops

Attached is a letter from Henry Curtis about his own hop growing experiences in the early 20th century.

Stoney Acres, Brushton, N.Y. 12916

October 29th, 1970

Not knowing to whom this should be addressed, I am just hoping it will reach the young men who interviewed me. When you asked me what type of farming was done by my Grandfather’s farm, I said it was dairy. That was true for the last few years but for many years before that the main crop was hops. Hop raising was very demanding work, starting as soon as the frost was out of the ground and lasted until after frosts came in the Fall.

By the time that little sprouts appeared in the hop hills, the first job was to make two holes in each hill by a special bar. The poles from ten to twelve feet long was set in the holes. When the new vines were two to three feet long they had to be tied to the poles, this was done two or three times before the vines developed enough so that their tendrils would cling to the poles by themselves. In the meantime a constant cultivation was kept up. No weeds were allowed to grow.

This labor reached its climax about September when picking time came. Hugh boxes were brought into the field, a pole with a crotch at the top was driven into the ground at each end of the box. Vines were cut near the ground, then the hop pole was pulled the from the ground and placed butt end on the ground and resting in the crotch of the upright, the pole with its vine over the box, one at each end, then from two to six men women and larger children

picked the hops from the vines. As they finished picking from those poles the cry went up POLE and soon other poles were in place.

Many of the pickers came from Canada who came every year for that work but friends and relatives also came so the evenings were quite gay. After a hearty supper came dancing, songs, stories, games etc. Our big event that I always looked forward to was roasting late corn over the embers in the heating room in the kiln where the hops were dried.

The fun could not last too long though as five o’clock came early next morning. Everyone was ready for bed soon.

The kiln where the hops were fired was equipped with two huge stoves on the first floor. Fires were kept roaring in

them constantly. The floor above was just narrow strips, leaving space between them, this was covered with burlap so hear from below could reach all the hops.

In addition to the extreme heat sticks of brimstone was put in pans a top of the stoves. This was to bleach the hops.

The brimstone was dropped on the stove and then the fireman made a dash to get outside. When the picking was completed and hops all dried, the poles had to be stripped of vines, then stacked together ready for spring, the vines gathered and burned clearing the field. Later the dried hops had to be baled and covered with burlap well sewed on. These bales weighed several hundred pounds each. Now they were ready for the market.

Hop raising was quite a gamble, some years they would not bring in enough cash to pay expenses, other years they might bring in more profit than the value of the whole farm. The climax of this was when the price went to $1.00 or more a pound. That made a topic of conversation for years but I don’t think it was ever repeated.

Please overlook the errors in typing. I don’t do it often and use the one finger hunt and punch system.

HENRY CURTIS **

Dear Mr. Curtis,

Thank you for signing the release and the added material you sent. We are always glad to gain

more material on the area and are very pleased with the generosity of the people in Northern New York.

Thank you again and I hope you are feeling well.

Cordially yours,

William J. Langlois,

Director

8. List of other interviewees who talk about growing hops in

Franklin County

- Floyd Earle (1887-1974)

- Fred Maloney (1890-1977)

- Joseph Dufrane (1868-1972)

- Glen Dickinson (1896-1974)

- Henry Curtis (1876-1971)

- Hollis Foote (1888 -1972)

- Mattie Haskins (1897-1976)

- Pearl Leonard (1895-1986

- Orville Langlois (1877-1975)

- Maruice Brown (1902-1983)

- Eugene Bordeaux (1895-1982)

- Thomas Campbell (1886-1981)

9. Other Documents

See: Thomas Rumney, “A Search For Economic Alternatives: Hops in Franklin

County, New York, During the Nineteenth Century.”