Published in the Franklin Historical Review Volume 46 2011

A Personal Retrospective on Collecting Oral History 40 Years Ago

– and Making that Material Available to Today’s Researchers

William J. Langlois and Robert H. McGowan[1]

In late December, 1968, the authors began recording an oral history of the largely abandoned Franklin County mill and logging town of Reynoldston.[2] Oral history was a “new” approach to preserving history and seemed like an appropriate means of capturing the history of this small community from the people who had directly experienced it. From the beginning both of us were taken with this historical method and were genuinely excited by the opportunity to collect and document the history of our area. It should be remembered that at the time, in the relative early days of oral history, most historians and researchers took a somewhat jaundiced view of this novel method. Somewhat surprisingly, we both found academic sponsors at our respective institutions willing to support our efforts.

We first interviewed Eugene and Daisy French Bordeaux, Bill’s grandparents, two of only a few people then living in Reynoldston. They were a good choice for our first interviews, as they were willing to be patient with us as we learned the ins and outs of interviewing. During vacations over the next year we collected over 60 hours of tape from 17 people. This group comprised most of the surviving residents who had lived and worked in Reynoldston during its most active years (1890-1930). In addition we collected historical photographs and documents that the interviewees had preserved. We were genuinely surprised by the openness and candor of the informants and their willingness to share details of their lives in Reynoldston with us. Their support and trust in us allowed for collecting personal information that would never have been shared with an outsider.

From the beginning we made the conscious decision to collect as much social history as we could. We both believed that we were giving a voice to people whose lives were rarely documented in conventional histories. We were trying to capture enough detail to enable us to create a rounded picture of life in this French Canadian, Scottish, English community whose population peaked at about 350 people in 1915. This effort led to long lists of detailed questions about topics such as home remedies, religious beliefs, and the chores of daily life in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries.

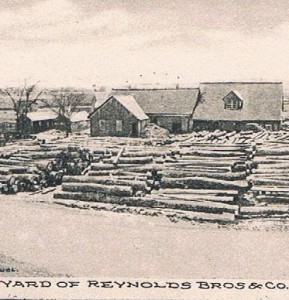

In addition, we attempted to document the business dealings of the Reynolds Brothers Mill and Logging operations. We were definitely hindered in this, since none of the actual business partners were alive and few of the business records had survived. People who had worked as loggers and mill hands for the Reynolds were alive, however, allowing us to document the history and operation of the lumber mill. We also focused on life and work in the Reynolds’ logging camps, including everything from diet to cleanliness to the processes of logging. Often, we wondered if anyone would ever be interested in so much detail about daily life in an isolated mill and logging community in Northern New York State.

In the summer of 1970, we lived in Bill’s grandparent’s Reynoldston camp (no running water, no electricity), while expanding our oral history project to include interviews with a wider range of people from across northern Franklin County: Malone, Bangor, Constable, Westville, and Duane (we call these interviews the Franklin County Oral History Tapes). We set out to interview as broad a cross section of people as possible and continued our focus on social history and documenting peoples’ work and daily lives. That summer an additional 100 hours of tapes were collected, of which about one third were later transcribed.

Late in 1969 we received a research grant from the State University of New York to further our work, and in 1970 we formalized our local history research project as Reynoldston Research and Studies, This funding allowed us to have better tapes and tape recorders. We also found new support from Special Collections at SUNY Plattsburgh, the Oral History Program at Cornell University, and the Folklife Program at Cooperstown, NY.

In the same year we published an article about our work in the Franklin Historical Review, Volume 7, pps. 53-55. This article still resonates with us today and, using local examples, lays out the case for the “New Social History” of the 1970’s and ‘80’s. It explains in some detail how we approached our work on Reynoldston and the collecting of oral history interviews. To quote:

“A cultural history should record everything that has impinged on a person, in a group, and been passed from generation to generation. Cultural history therefore, is not only concerned with modes of thought and belief, but with the most minute features of everyday life…”[3]

For students of social history we believe our oral history material will both be surprising and revealing. In our youthfulness we never shied from asking the most personal questions about dating, sex, marriage, family, religion and societal attitudes. These and many of the topics we pursued were not commonly talked about, let alone tape recorded, in 1969-71 by residents of Northern New York State. Our personal connections helped to establish trust between us and interviewees, and perhaps, since we were young college students, people did not take offence to our prying questions. Surprisingly, no one ever refused to answer our endless questions.

Also, in that now long-ago summer of 1970, we drafted a book manuscript based on the Reynoldston interviews. We were determined to include in the book all the social history in minute detail that we had amassed in our interviews. And as might be predictable, the initial comments on the manuscript were that we had way too much detail that probably would not be of great interest. Of course that was when this material was not too far removed for many people who were still alive and had experienced it. In the next phase of our work, we hope to finish our book manuscript for publication.

After graduating from college in 1971, we embarked on separate careers, lived on opposite coasts, and lost touch. Luckily, 98% of the tapes and transcripts were preserved in several locations on both coasts. In 2009, when Bill Langlois retired, we resumed work on the body of material we had collected 40 years earlier. By then all of our informants had died, and our material and tape technology had become genuinely old. Since the tapes were created over forty years ago and most informants at that time were in their late seventies to early nineties, the interviews preserved detailed first-hand accounts of life in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries in Northern New York State and in some cases included second hand stories of life around the time of the American Civil War. Much of the material on these tapes record past ways of life and earning a living that are foreign to most people in the technology driven 21st Century. Equally important is that this material documents a part of New York State that has never been fully studied by researchers or other academics.

We soon realized that due to modern technology, there is a new opportunity to use and share this material. The ability to digitize tapes, transcripts, photographs and documents will help to ensure that this material survives in perpetuity. Additionally, the internet provides a whole range of new opportunities to share our material with others on a global scale. The original copies of all our material will eventually be deposited in Special Collections at SUNY Plattsburgh.

Since 2009 we have focused on the Reynoldston tapes. Transcription of the 17 Reynoldston interviews, and totaling sixty hours of tape, has only been completed within the last two years. These transcripts also now exist in digital formats. Most of the transcribed Reynoldston interviews have been indexed, and the indexes are available on the Reynoldston website. In reviewing the interviews after 40 years, we were impressed by the consistency of our respondents, who seldom if ever contradicted each other even on minor points. Today, it is now easier to verify and clarify details and dates than it was in the 1960s, as many historical newspapers and other records are now online. Since 2009 we have also collected an additional 200 photographs, bringing our holdings to more than 400 photos of early Reynoldston people and places. All of those photos have been digitized and identified. Also, all the Reynoldston interview tapes have been transferred to digital formats, including compact discs. This will ensure that the material will survive in case the reel to reel tapes degrade over time. As well, it will allow us to share the audio material and the distinct speaking styles of the interviewees through the internet.

We have also found that research in the Franklin County land records has revealed much new information on the growth and the ultimate break-up of the Reynolds landholdings. The land records have recently yielded the initial contract between Reynolds Brothers and the Brooklyn Cooperage Company, a contract that ushered in Reynoldston’s busiest and most prosperous period (1908-18). The contract provided much needed specificity about the business relationship between Reynolds Brothers and Brooklyn Cooperage Company. When Brooklyn Cooperage bought logs from Reynolds Brothers to make barrels for transporting sugar it connected Reynoldston to the larger national and even world economies.

This summer we have moved from the Reynoldston tapes to focus on the digitization and preservation of the one hundred hours of Franklin County tapes. By the end of June all tapes and most of the existing transcripts will be digitized. Then more of the Franklin County tapes will be transcribed over the next few months. We have been truly pleased that we have engaged a recent graduate of the University of Victoria in BC, Mr. Tyson Rosberg, who has on his own developed an interest in oral history, to carry on this project with us. We have expanded our research on all transcripts to include land records, genealogies, newspapers, related online archives, and maps. We are attempting to establish personal contact with descendants of our original thirty or so interviewees.

In April 2010, based on old and new material, we launched a website dedicated to Reynoldston – http://www.reynoldstonnewyork.org. The website summarizes the history, life, and work not only of Reynoldston people, but of Reynolds Brothers, Inc., the logging company and economic engine for the town. The website contains a wealth of historical photos, documents and interview materials that are now accessible to family descendants, students and researchers. In slightly more than a year over 7,000 people have visited the website and viewed over 14,000 pages of content. The website contains quotes from interviews, and a list of the Reynoldston and Franklin County Tapes, plus some of the transcript texts as well. Because of the volume of material now available, we plan to eventually update this website, to include the text of all or most of both the Reynoldston and Franklin County transcripts, and access to the audio tapes. The new website content will be more searchable then the current one.

Working with oral history forty years later has given us new insights into both collecting and using oral history. It has taught us the importance of contextualizing interviews. When creating oral history, it is vitally important that the interviewer document the family background of the interviewee in some detail. For example, without background information it is difficult to find people in census and other records, especially if they have chosen to abbreviate their names or changed their names upon marriage or re-marriage. In addition, interviewers should realize that many family names, place names and even physical landmarks change over time. This has happened in our case, as much of our information is over 100 years old. For example, “Cook’s Corners”, which figures in some reminiscences that we recorded, is no longer on maps, if it ever was. We have had to rely on our own knowledge to locate it, but other researchers might be at a loss without contextual information to support the information in the transcript.

After the interview is finished the interviewer should record details of their relationship to the interviewee and record any personal recollection they might have of the person. Whenever possible both current and historical photographs of the interviewee should be collected. In the digital age, this is so much easier than it was forty years ago. Similarly, the interviewer should provide a detailed description of the physical environment and circumstances of the interview. This type of background will enable future users of the material to better understand the context of the material and the interview process. When we collected our material, due to our youth and inexperience, we did not realize how fast things would change. Now as we go back to the area and continue our work, we are well aware that much that we took for granted is now gone, with little or no documentation.

In Conclusion:

In 1970 oral history was new and few of us collecting interviews realized that one day the material would become “old” and an important source of historical information for future generations. We are lucky that we were young then and now have the opportunity to fill in some of these gaps and provide additional documentation for the interviews long after the interviewees have passed on.

We believe the Reynoldston project is one of the most in-depth studies of a late 19th – early 20th century mill and logging town ever undertaken. We hope that by closely studying Reynoldston, insights valid for the economy and society of the North Country as a whole will emerge. While logging has been discussed in many local and regional Adirondack histories, our detailed focus on the growth and decline of a specific logging company, such as Reynolds Brothers, Inc., and on the social and economic history of a logging community may be unique. We also hope that our Franklin County tapes and transcripts will prove a useful resource for those interested in a grass-roots social history of the North Country when it flourished in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries.

We are constantly seeking new material on Reynoldston, and on our Franklin County interviewees. A list of all the people we interviewed is below. Please contact Bill through the contact form on the website if you have information to share with this project. http://www.reynoldstonnewyork.org

Mr. & Mrs. Eugene and Daisy Bordeaux

Mrs. Lillian Prue

Mrs. Ann Desparois

Mr. Ealon Bordeaux

Mr. and Mrs. Tom and Jenny Campbell

Mrs. Eugenia Lashomb

Mr. Danford Whitcomb

Mrs. Delia Moquin

Mrs. Frances Ellis

Mrs. Beatrice Beaman

Mrs. Haidee Rushlow

Mrs. Lillian Barber

Mr. Orville Langlois

Mr. Harold McGowan

Honorable Clarence Evans Kilburn

Mrs. F.R. (Elizabeth Crooks) Kirk

Miss Ola Stockwell

Mr. Henry A. Curtis

Mrs. Barry (Alice H. Bowen) Crooks

Mr. Glenn Dickinson

Mr. Peter Callahan

Mr. Clifford Berry

Mrs. Mattie Haskins

Miss Katy Long

Mr. Hollis Foote

Miss Pearl Learned

Mr. Floyd A. Earle

Mrs. Lillian Lawrence

Mr. and Mrs. George H. Chapman (Katherine M Cushman)

Miss Anne Beckenauld

Mr. Joseph Dufrane

Mr. Leo J. Tobey

Mr. James Smith

Mrs. Abbie E. Cantwell

Mr. Fred Maloney

Mr. George H. Russell

Mrs. Samantha Marlowe

One response to “A Personal Retrospective on Collecting Oral History 40 Years Ago”

[…] A Personal Retrospective on Collecting Oral History 40 Years Ago […]