Brief History of Malone, NY

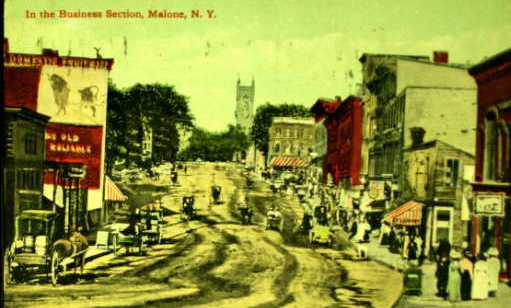

Malone, Main Street, 1907

In 1807, New England settlers founded the First Congregational Church in what was to become the Village of Malone; this congregation was the first organized religious body in Franklin County. The area around Malone had actually been first surveyed several years earlier, in 1801, by Joseph Beman of Georgia, Vermont, on behalf of Richard Harison who had purchased a large tract of land in the region of Northern New York. Richard Harison was born in 1747 and was a lawyer and Federal Politician from New York City. The land he purchased had originally been part of the area known as ‘Macomb’s Purchase’—an immense amount of territory of some 3,670,715 acresacquired from the state in 1791 by Alexander Macomb, a merchant who gained financially during the American Revolution.

The first settlers began arriving in Malone in 1802, and included Enos, Nathan and John Wood, Noel Conger and Noah Moody—all from Vermont. The 1801 survey of the land laid out city lots along what is now Main and Webster Streets; from its initial origins, Main Street was designated as the commercial and business district of the town, while Webster Street was intended as residential. The outskirts of Malone surrounding the Salmon River was referred to as “The Center” for many years, although its official name was originally Harrison, then changing to Ezraville in 1808, and then finally incorporated as Malone in 1812.

In the following years, Catholic settlers from Ireland and Quebec filtered in and the homogeneous “perfect Puritan village”–as one early resident described it–experienced some religious and ethnic tension. Seaver’s Historical Sketches of Franklin County recounts that Ashbel Parmelee (1784-1862), the Congregational Church’s first pastor, succeeded in expelling a Catholic priest from the village and thus it can be inferred that the French and Irish presence in Malone was real, albeit small and relatively powerless in the years before 1845.

Malone Main Street -1907 from Postcard

Beginning in the 1840’s a number of railways were constructed in the area, including the Northern (later Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain) Railroad, which opened in 1850 and which was bought by the Rutland Railway in 1901 and closed in 1968, and the Mohawk and Malone (later New York Central), which ran North-South through the county and opened in 1892 and closed in 1968 as well. The famous Water Level Route of the New York Central, which ran from New York City to upstate New York, was the first four-track long distance railroad in the world. These new transportation routes dramatically expanded the area’s access to markets for the local dairy industry, at the time, probably the single largest economic driver for northern New York and Franklin County.Their arrival ushered in a new era of commercial and economic growth for Malone. In addition the new railroads located their repair car shops and operational offices in Malone thus creating numerous jobs. This period of economic growth also spurred a higher level of immigration into the area.

By the 1850’s, French and Irish settlers were arriving in Malone in significant numbers. The Irish Potato Famine of the 1840’s and the near collapse of Quebec’s economy in the 1870’s hastened this immigration; the closeness of the Canadian border also made it easy for both Habitant Quebecois and Irish families docking in Montreal to cross the border into New York. Malone was one of the first places they reached and the coming of the railroads made manufacturing and milling more economic and created jobs in Malone for both long-time residents and new arrivals, making it a popular place for settlement by new immigrants. Irish immigrants tended to gravitate towards occupations in the railroads, mills, and farms, while their French Canadian counterparts tended to seek work in the logging woods and as day laborers.

The close of the 19th century was a particular expansion time for both the United States and for Malone. The rich farmland to the north of Malone and the abundant forests to the south helped to fuel the local boom. Moreover, the opening up of the American west and transportation in the form of new railways helped to create economic prosperity. Locally, part of this prosperity was due to the rapid increase in the price of hops. Hops were an easy cash crop, suited to the climate, which helped to supplement and expand an already well-established farming economy; soon many of the farms around the town and throughout the northern part of the county began to engage on some level in hop production.[1]Hop growing continued, although at declining levels, into the mid-20th century.

Both the so-called “French Church” (Notre Dame—with its stained glass windows donated by the French “Forestiers”) and the “Irish Church” (St. Joseph’s) date from the post-Civil War period. Not to be outdone, in 1883 the Yankees erected the third building of the First Congregational Church on the same site on Main Street, which still dominates the village landscape—no doubt as its architect intended. Even now, visitors to Malone are always struck by the many excessively large homes that grace Elm Street, Main Street, Milwaukee Street, and Constable Street. These large, ornate Victorian and Edwardian-styled homes reflect the economic success of their former owners.

Indeed, as early as 1806 the citizens of Malone desired a centre for higher education and built Harrison Academy to instruct the children of the increasingly wealthy families of the town; this institution operated as a private, rather than public school, and attempts were made in 1831 to make the academy more public. The first Franklin Academy was erected in that year, replacing Harrison Academy, and was built with funds derived from mortgages taken out on the homes and farms of 73 families. The current Holy Family private Catholic school has grown out of the long tradition of Catholic education in Malone. Later in the century, in 1884, Henry Rider opened the Northern New York Institution for Deaf-Mutes in Malone and rapidly expanded enrollment, filling a need for specialized education in the North Country. At its peak, the school occupied an extensive campus of several buildings and a working farm, and the institution continued to function well into the mid-20th century when the integration of special education into the public schools lessened the need for a separate educational institution.

Congregational Church, Malone, NY

The turn of the 20th century continued the physical and economic growth of Malone. In 1900, the population was at 10,000 and by 1915 this number had risen to over 11,000 of which Irish and French families together comprised a large majority. Also by the early 1900’s a number of factories and industries, including Ballard Mill, McMillan Woolen Mill, the Tru-Stitch Moccasin Co., the Bronze Powder Works, and the Malone Paper Company had set up in the area and were employing large numbers of Malone’s citizens. The well-established farms, which had long been the traditional basis of the area’s economy, and their related feed stores and markets also provided considerable employment in Malone, as did the retail, banking, and county government that began as the town developed and grew over the course of the previous century. A number of Malone’s citizens served in World War I, beginning with the American entry into the war in 1917 (although some volunteered earlier in 1916), and Malone’s economy continued to boom, reaching its height in the early post-war 1920’s.

In the 1920’s, Malone’s proximity to the Canadian border shaped its history in another form—bootlegging. American prohibition (1920-1933) was at its height in this period and Malone’s very closeness to Canada made it an active area for bootlegging. While prohibition had been in place earlier in Canada, by 1925 most of the Canadian provinces had repealed the legislation and Canada represented a cheap and easily accessible market for liquor. Congressmen Clarence Kilburn (1893-1975), a resident of Malone, recalls that Malone was nearly taken over by prohibition agents in their attempt to stop the illegal sale of liquor, but their attempts did little to hinder the extravagant nightlife parties of the area which were held at areas such as the Elks Club. Likewise, Fred Maloney (1889-1974), another resident of Franklin County, recalls smuggling brandy and other spirits out of Canada through farms that straddled the Canadian-American boarder, some of which exploits routinely ended with being shot at by both probation agents and the state troopers.

The onset of the Great Depression following the collapse of the American stock market in 1929 ushered in a period of economic decline for Malone, which was still largely dominated by primary-sector industries such as logging and milling. The Second World War briefly revitalized the town, however, in the post-war period of the 1950’s and beyond Malone went through a gradual period of decline as no new industries or businesses replaced those of the earlier century. By the end of the 20th century most of these old job sources were gone and prisons on the outskirts of town represented the only really strong source of employment. While some of the previous grandeur of Main Street has been lost to fire and decay Malone is still recognizably the thriving and industrious 19th century town it once was. As of the 2000 Census, 14,981 people reside in Malone—only 4000 more than at the town’s height in the late 1910’s and 1920’s.

[1] Hops were an important cash crop of the late 19thcentury and which were exported to brewers in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Hops represented not only an important part of Malone’s economy, but also an important part of its culture as dances, songs, and harvest parties developed around the annual picking. This industry was one of the few in the area in which labor was dominated predominantly by women and children.

Edited by:

W. Langlois, R.H. McGowan & Tyson Rosberg

Special Thanks fo the Franklin County Historical & Musuem Society for the inlcusion of some of their material.